by Irina Carnat

As many fellow researchers or others simply curious about the latest “gadgets” in AI-driven applications, I too got to try out ChatGPT (a variant of the Generative Pretrained Transformer). It is the latest version of OpenAI’s Large-scale Language Model: for laymen, it is a chatbot (although “it” wants to make sure not to be considered a mere chatbot, but “a machine learning model that can generate human-like text based on a given prompt. It can be used to generate responses to user input, making it a useful tool for building chatbots and other conversational systems”.)

Like a nostalgic flashback, the hype and enthusiasm around ChatGPT brought me to my childhood years when all the kids used to talk about the newest released videogame or Harry Potter DVD we got under the Christmas tree.

Besides the fact that everyone talked about it, three main reasons convinced me to try it out (not necessarily in this order):

- It came from a well-regarded company in AI applications

- It came for free and available to everyone

- It came with great expectations

After trying it during the Christmas holidays, pretending it was a Christmas gift for grown-up academics, I decided to share a few personal considerations, while still preserving a holiday-like (albeit skeptical) mood.

# 1: Not all gifts come from the heart (let alone if from Silicon Valley)

Those of us who do not believe in magic and old bearded philanthropists who climb down the chimney, we all know that gifts ultimately from someone who has our best interest at heart: a parent, relative or friend who just happens to know what we want or need. For this reason, we can at least reasonably believe that if a gift entered our house, it is not harmful: we would not allow strangers to enter the privacy of our homes, let alone approach our beloved Christmas trees, thus a gift usually comes from someone we trust.

OpenAI gained its reputation and popularity from being an AI research and deployment company, with the mission to ensure that Artificial Intelligence benefits all of humanity. Since its foundation in 2015, its most famous applications include:

• Access GPT-3, which performs a variety of natural language tasks

• Codex, which translates natural language to code

• DALL·E, which creates and edits original images.

In particular, ChatGPT was released in November 2022 and gained 1million users in 6 days! Such popularity is due to its general effectiveness and user-friendly interface. Some have even argued that it may even replace Google [1] and get a Chrome extension [2].

But this is the trick with trust when we talk about Artificial Intelligence:

The concept of Trustworthy AI, and generally building trust in technology, is a buzzword that we should be wary of. The fact that such a ‘gift’ comes from a well-respected company, that allegedly promotes AI for the benefit of all the humanity, and implicitly challenges the quasi-monopoly of less well-respected search engines, we tend to trust them more and start ‘playing’ with these new gadgets lightheartedly. The truth is that, until such trust is well-earned and deserved, we should not lower our guard. After all, even OpenAI and was born in Silicon Valley, a place from other less well-respected companies came from with less trustworthy intensions, and lots of money [3].

#2: Not all gifts come for free (none of them do, or at least not immediately)

In a capitalist society, no gifts are actually free: someone must have paid a price for its production, and in a surveillance capitalistic society [4], you pay it twice. Some say that (personal) data are the currency of the XXI century. According to OpenAI’s Privacy Policy, they “may collect Personal Information if you create an account to use our Services”. Yet, creating an account is a prerequisite for using the Service, so personal data will be ultimately collected for the mentioned purposes (See Privacy Policy here: [5]).

However, in the case of ChatGPT, it may need to monetize later on. And the price we “pay” today is simply making it better to be sold later on. This needs a few words of explanation:

The way a Generative Pretrained Model works is by reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), where human trainers of the AI model provide conversations in which they played both sides—the user and the AI assistant.

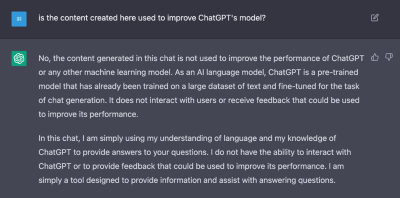

However, even after the model has been trained, machine learning models benefit from continuously learning over time. In a nutshell, even the iterations that take place in the chats are used to improve the model.

Although ChatGPT itself denies the accusations…

OpenAI’s Terms of Use, a legally binding contract, (at Article 3, (c) Use of Content to Improve Services here: [6]) explicitly states that Content created by the users is indeed used to improve model performance, and even provides a link for additional information (and instructions to opt-out). At least in this case, ChatGPT would have failed the Bar Exam…[7]

Plus, as for other OpenAI APIs[8]., the clause 4. Fees and Payments clause in the Terms of Use may be someday applicable to ChatGPT too.

If we all contribute to make the technology better so that it can be – eventually sold for a higher profit – why should we pay for it later? This may be an uneasy (almost ethical) question to be answered.

#3 Not all gifts are good for you (but you may not know it, yet)

Nonetheless, upon the promise of unprecedented performance and hype around this new toy I (felt like I) got under the Christmas tree, I too started to play with it.

The rules were easy:

- Create an account.

- Chat

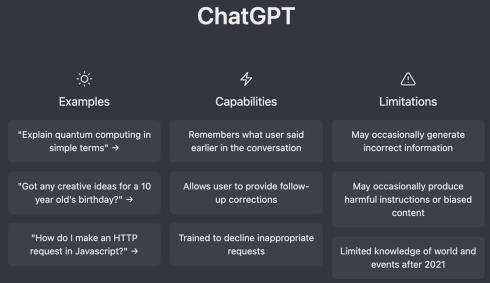

The home page contained Examples, Capabilities and Limitations.

First, as a PhD student I was curious how well it would summarize a text and provide information on a given topic (you know, papers, articles, etc). I played with it, it worked marvelously, but don’t get too excited yet. I immediately started to test its potentials and limits, with genuine curiosity and critical sensibility.

- Simply put, if you ask to summarize a text, it might still omit certain important factors as it does not “account for” the logics used. As such, it lacks explainability.

- When asked general questions, such as “how to quit smoking?”, it provided a numbered list with all the common sense the Internet can provide, whereas with certain more “personal” questions, such as “Should I quit my job?”, even when provided with some more details, the answer was still a very generic numbered list that can be summarized as “it depends on your personal goals and individual circumstances”. Honestly, it is a relief that it is not capable of sentiment analysis and does not use any other of my personal data to provide a more accurate answer. Not yet.

- When asked a more technical question, such as “Which AI explainability methods are there?”, the answer is correct, complete and accurate, BUT, there is no way to find out which sources have been used.

So, here is the trick: even if the user is provided with the explanation on how ChatGPT works from the technical standpoint, neither the nature of the datasets used for training the model, nor their sources are disclosed. This does not allow for an assessment of the reliability and soundness of the answers provided. For instance, in the last question about the explainability methods, there is great difference in knowing whether the answer is based on sources from amatorial blogs or scientific papers. Afterall, it is fundamentally just a chatbot…

Certainly, at this stage ChatGPT is not considered an AI system capable of heavily impacting high-stake rights and freedoms. Not yet. There was no impact assessment carried out to assess the risk that such an AI-driven tool would have on society. Nonetheless, there have already been speculations on its potential disruptive effect on certain societal sectors, such as education [9], the job market [10], scientific research [11], etc.

This leads me personally to the conclusion that technological neutrality is a myth and any AI application must undergo a thorough and serious evaluation to guarantee its safety. Surely it is just a conversational tool and it may not be used as a decision-making tool in high-stake scenarios, for instance in public institutions. However, it may play a central role in people’s everyday lives, in how they write an email, make a research, think, or get informed.

The road ahead is still long, but as technology advances at an unprecedented pace, regulation falls behind, as do we all. In this context, these “performance-enhancing” technologies become appealing to the point where we cannot help but rely on them.

Now that such a gift had been put under my Christmas tree, I wish I could keep playing with it, as long as it is safe and the rules of the game have been disclosed/agreed upon.

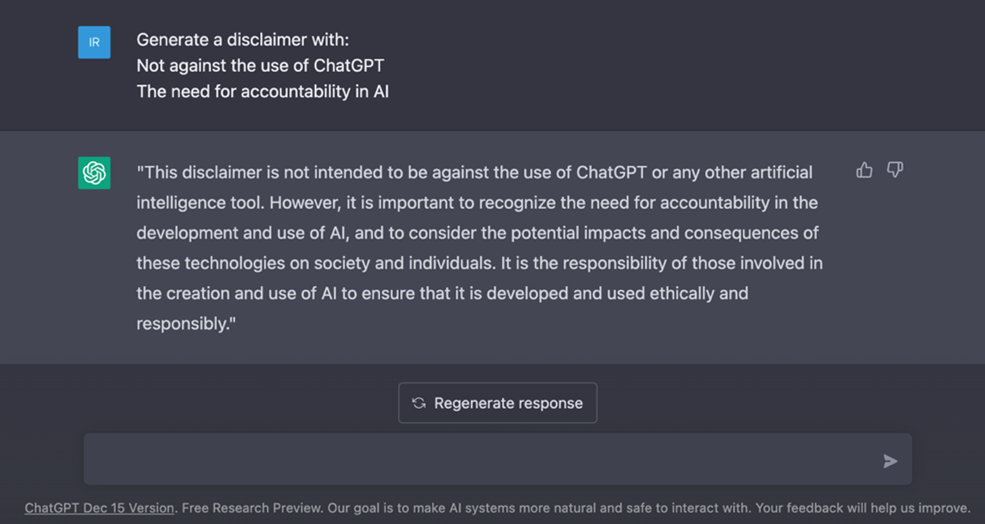

As a conclusive (self-explanatory) remark, I will leave you with this final disclaimer:

Sure, it is still imperfect (like in its use of the word “disclaimer”), but you get the idea.

And – perhaps most importantly – now you may find yourself questioning how many of all the previous paragraphs have been written with the support of this chatbot. Yet, for all the considerations expressed above, you may not have the right to know it while I may not have the obligation to tell, and this is precisely where things get interesting.

Stay tuned!

Irina Carnat,

PhD Student and researcher in Artificial Intelligence for Society at Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna and Univeristy of Pisa